Petroplague: Oil-eating Microbes

For the

most part, I prefer walking along rows and rows of books in bookstores to

online shopping. Ebooks, not being on real bookshelves, don’t currently have much of a

chance with this non-nook, non-kindle, non-ipad, I-want-to-turn-an-actual-page reader.

However, I may need to change. Many great science ebooks and many works

of fiction with science are available only in digital format, and Petroplague

has gotten my attention. There are no zombies. There is gas and a petrol-feasting

organism that jeopardizes the way we live. This was a different plague. I read…<gasp>…PDF.

The

title didn’t grab me, nor did the cover

art. But the author did. Here is my disclaimer: I’ve

corresponded with Amy Rogers, so there may be bias.

The

title didn’t grab me, nor did the cover

art. But the author did. Here is my disclaimer: I’ve

corresponded with Amy Rogers, so there may be bias. I started my correspondence with her (or her with me) because of our shared passion and enthusiasm for science and science writing. It drips off her. It runs through her website and into her support of other authors. I’m sure the enthusiasm runs into her home-life too, into her family and children—they will benefit immensely from her.

So,

because of Amy and her enthusiasm, I read. I found great microbial science,

oil-eating microbes running amuck, a well thought-out Los Angeles landscape,

children’s stories and songs, references to art, and characters who grew with knowledge. Here is what Amazon says

about her:

Amy Rogers, M.D.,

Ph.D., began her writing career in elementary school by (unsuccessfully)

submitting anecdotes to Reader's Digest in hopes of earning twenty-five bucks.

By junior high her real passion was science, especially microbiology. In the

bedroom of her home in rural southern Minnesota, she kept Petri dishes of

bacteria in an egg incubator and won purple ribbons in science fairs. That

passion led her to study biochemistry at Harvard, and ultimately to earn a

doctorate in immunology. Wee beasties animated her years of teaching

microbiology at the university level. More recently, micro-critters inspired

her to write novels and short stories that highlight their amazing powers.

Amy's thrilling science-themed

novels pose frightening "what if?" questions. Compelling characters

and fictionalized science--not science fiction--make her books page-turners

that seamlessly blend reality and imagination. Relentlessly curious, Dr. Rogers

works for scientific literacy and nature education for kids.

This author loves dim

sum, Ted Drewes, redwood forests, Minnesota lakes, Hawaiian beaches, and cats.

She lives in Northern California with her husband and two exceptional children

who believe she has an unreasonable tolerance for mysterious things growing in

her refrigerator.

What is

not to like?

|

| From Wikipedia: La Brea tar pits |

Within

the text, there is an exhibition of contagion theory and the growth of

microorganisms…

“Christina cordoned

off her grief and started to work. She picked up a bacterial culture needle—a

thin platinum wire mounted on a pencil-like handle—and lifted the wire into the

hottest part of the burner flame until the metal glowed red. After allowing the

wire to cool in the air, she plunged it into a flask of cloudy yellow

liquid: an old culture of the

photosynthetic E. coli bacteria. Then

she dipped the tip of the wire into a tube of fresh sterile broth. To the naked

eye the wire looked clean, but Christina knew it was covered with thousands of

invisible bacteria that would slip off into the fresh food and begin to grow

vigorously, doubling in number every half hour. Only a touch was all it took to

spread bacteria from one liquid to another.”

And Petroplague

outlines well in the following three scenes how microorganisms can potentially

spread and lead to disaster:

“He poured about a

half cup into the borehole, and the plague-infected fuel disappeared into the

depths. Jack expected to repeat this process all the way to Mission by looping

back east across the valley floor to the city of Bakersfield and to the Kern

River oil field where he knew pump jacks covered the arid plain as thick as

paparazzi around an A-list celebrity.

The rod on the

contaminated pump jack rose and fell, rose and fell as Manley and Jack strolled

away.”

And

And

“When unfolded, the

gauge stick was twelve feet long. Ronny lowered it through the port and dipped

it into the gas. The overfill alarm was right; the tank was nearly full. He

refolded the stick and kept it handy because he’d be using it at the stations

he visited next. Then he sealed the access port, packed up the gas hose, and

wheeled his tanker tuck back on the road.”

And this scene in which a mechanical “pig” is used to run through fuel lines to check their integrity:

And this scene in which a mechanical “pig” is used to run through fuel lines to check their integrity:

“Did you bring the

pig, Al?” Ken asked.

“Wouldn’t be doing my

job if I didn’t,” Al replied. “I’m the pig keeper.”

They both smiled at

his joke.

“These smart pigs are

my babies,” Al continued. “The one in the truck is new. I used it for the first

time yesterday. Worked like a charm.”

”Which in-line

inspection did you use it for?”

“We ran the pig through the gasoline delivery

pipelines. Got data on the integrity of all the 87 and 89 octane pipes, from

storage tanks to trucks.”

”Then I expect the pig

will do a good job again today. We’ll run it through the jet fuel pipelines

from here to LAX. Program the pig to record information on metal loss and

corrosion, and temperature and pressure in the pipe. Of course if there are any

early signs of fracture, I want to know. Get pictures, if you can.”

”It’s as good as

done,” Al said.

Uh oh. Insert

ominous music here. Christina, the main character—a PhD. student

and Dr. Chen, her mentor, are working out the details:

They would get more

details from the DNA tests and the chemical analysis of the gasoline, but

Christina could no longer deny the facts. Her bacteria were eating L.A.’s gas.

Just before dawn,

Christina and her boss shared their data with each other. In laboratory

science, results were often ambiguous or conflicting, but their efforts tonight

had produced clean data and an inescapable conclusion. Dr. Chen looked

defeated, his shoulders sagging and his face wooden.

“I have to contact the

authorities. If the infection spreads…” He paused, and shuddered. “The

oil-eating bacteria mush not escape the L.A. basin. The city must be

quarantined.”

Is there

a solution? Dr. Chen leads Christina to a potential cure, but is it?

“…an antibiotic that

seems to affect Syntrophus.”

“I thought we tested

all the antibiotic classes and none of them worked.”

“This is a new

substance. I don’t have a clue what it is, I just know that it’s produced by

one of the microbes in our collection”

“From an oil field?”

“Yes. Presumably these

bacteria compete with each other in the wild, and one species evolved to make

an antibiotic that kills the other.”

Of

course, there are twists that I can not divulge. It is a thriller with disaster at every turn. And aside from the wonderful science, the characters grow throughout

the story.

Even the assumingly thick boyfriend of Christina’s cousin can grow—from a man who places grilled chicken on the same platter as the uncooked pieces—to a curious conversationalist regarding mutated bacteria.

Even the assumingly thick boyfriend of Christina’s cousin can grow—from a man who places grilled chicken on the same platter as the uncooked pieces—to a curious conversationalist regarding mutated bacteria.

“Mutated?”

“Not exactly. More

like, they learned a new skill from some friends.”

“We’re talking about

itty bity microbes here, right?” Mickey said.

“We are, but even bacteria have ways of

sharing information. The information is in the form of genetic material.

Bacteria can actually give some of their DNA to each other in a process called

horizontal gene transfer. It happens in the wild. Last night I found DNA in my Syntrophus that wasn’t there before. The

new DNA codes for aerobic survival.”

Don’t

worry. Aerobic is explained, but not pendantically. The story will show you what it is.

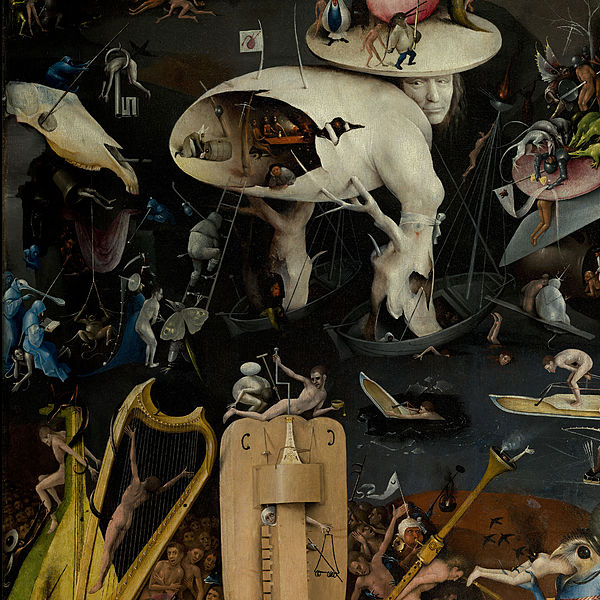

Also well placed within the story are details of microbiology experiments, details of what bioremediation is, description of bacterial predators, growth of microorganisms, PCR, and DNA hybridization and ELISA analysis, lateral genetic transfer…whew! It is not, however, written with the PhD in mind. It truly is written for all readers from high school on up (some middle schoolers may enjoy it too). Humor and references to children’s songs and stories and to artwork (nod to Hieronymus Bosch) added interest as well.

For the curious-minded who wish to learn more, end notes on various topics (i.e. collapsitarianism and lateral gene transfer) are provided. This is where Dr. Rogers explains how the real science was used in the story.

|

| A section of Hieronymus Bosch's dark and disturbing work;from Wikipedia |

For the curious-minded who wish to learn more, end notes on various topics (i.e. collapsitarianism and lateral gene transfer) are provided. This is where Dr. Rogers explains how the real science was used in the story.

In short, the science of the book holds high honors, channeling the work of Craig Venter and numerous bioremediation scientists. Petroplague explores what happens when the products of great and interesting science get into the wrong hands of ecoterrorists (and a greedy businessman).

I think Petroplague and the idea behind it is fantastic. And it can now sit on your bookshelf, or occupy space on your favorite ereader.

I read "Petroplague" a couple of months ago and it was a page-turner. Science and fiction are well balanced, and any 'geeky' stuff is well explained, so that the story will be intriguing even for readers who don't know much about microbes.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you enjoyed it too, and thanks for reading the review and sharing with others. I'm looking forward to her next WIP.

ReplyDelete